They Wrote the Book

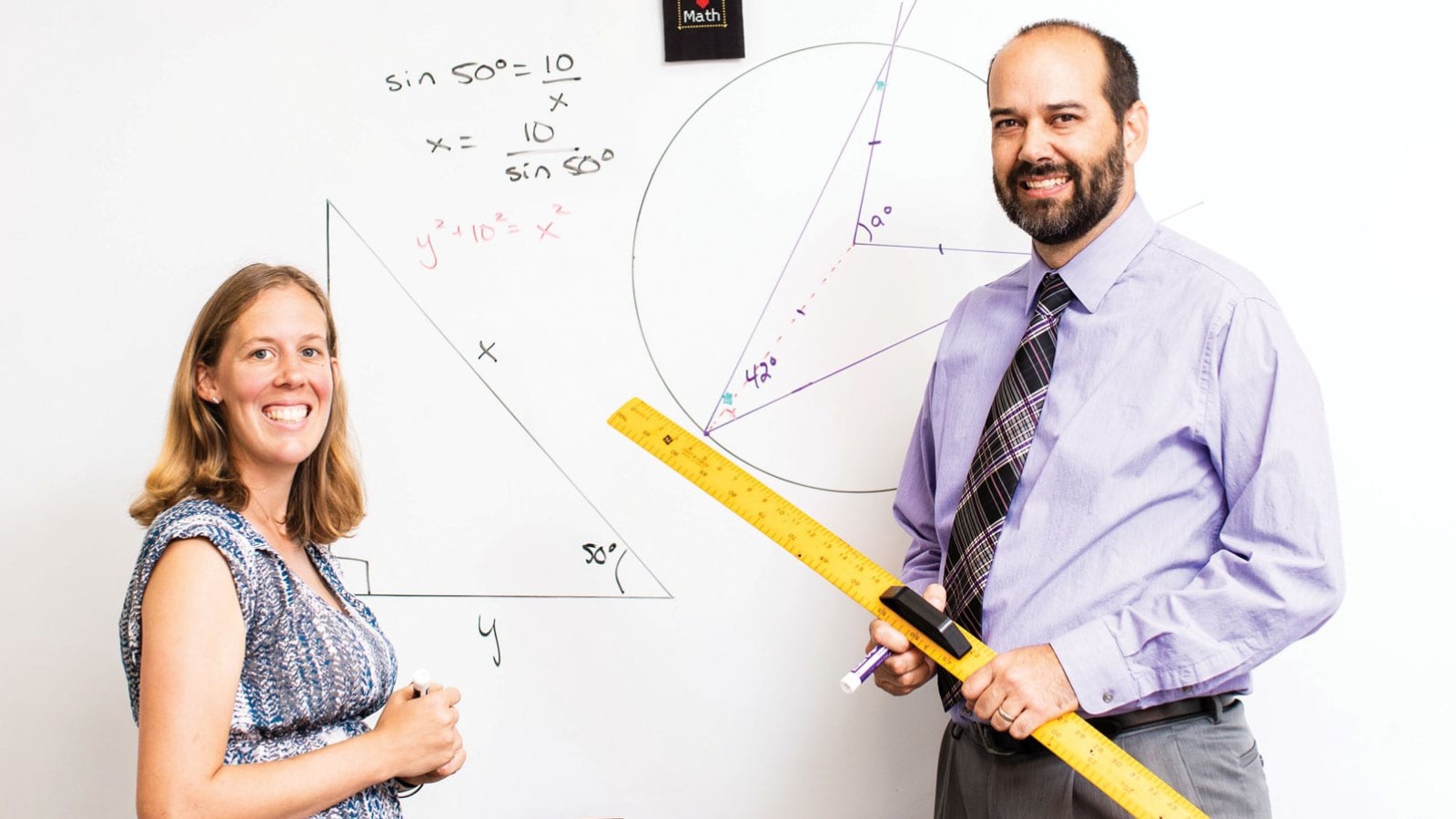

When Teddy and Karla Schaffer taught geometry at The Webb School in Tennessee, they used a textbook developed by a Deerfield Academy math teacher, Carmel Schettino. The book had some drawbacks that the couple worked around, but when they arrived at Williston in 2017, they knew something had to change: many of the math word problems celebrated the landmarks of a rival campus. “When we were in Tennessee, it didn’t matter, because no one knew what Deerfield was,” explains Mr. Schaffer, who teaches one section of Geometry Honors while Mrs. Schaffer teaches the other. “But once we were at Williston, we couldn’t use a Deerfield example.”

Their elegant solution: rewrite the book. Using a professional development grant, the couple last summer adapted and updated Ms. Schettino’s 700 geometry problems (many based on problems originally developed at Phillips Exeter Academy) and in the processs, swapped out Deerfield references and replaced them with namechecks from Williston’s campus. “Kristen leaves from the front of Mem West to walk directly to the crosswalk to the chapel,” begins one. “John is at the doorway of Reed and decides to meet Kristen along her path and walks toward the midpoint of Kristen’s path…” Williston teachers also make cameos in the book, as do students. “I’ll have a kid from last year poke his head into class,” Mr. Schaffer says, “and my students are like, ‘Oh, yeah, you were problem 273!’”

Creating their own customized math book not only allows the Schaffers to make yearly adjustments to their curriculum based on student response, but the book’s insider references also create a new level of student engagement. “The kids see examples in there, like a drawing that a student did, and they’ll say, ‘I know her, she’s in my grade,’” says Mr. Schaffer. “It gives a little connection.” Adds Mrs. Schaffer: “The book allows us to fit our kids. Exeter kids are different from Deerfield kids and different from ours, and we were able to shape it to fit where we want them to go.” Indeed, for this year’s edition, the couple plans to update the book with the names of students who actually are in their classes.

That kind of engagement and peer connection is particularly valuable in light of the teaching method used in Honors Geometry. Called problem-based learning, it relies on students to present their thinking to their peers, generating discussion and opening up opportunity for deeper discovery in the process. In class, the Schaffers select work from the previous night’s homework, and then let students have the floor. “Other kids can ask questions or make suggestions, or say, I did it a different way, or, I don’t think yours is right in this part,” Mr. Schaffer explains. “It takes a little more time and we don’t cover as much as we could with direct instruction, but it builds more depth. When someone just had a light-bulb moment the night before and they can share that, students learn better.”

The approach also builds social skills among the students, who are mostly eighth and ninth graders, Mr. Schaffer adds. “There’s a lot of social development that happens over the course of the year as they get more comfortable with each other. By the end, they are asking each other the questions and are teaching each other.”

Mr. Schaffer notes that the couple’s math book project has had another personal benefit: boosting their reputation among their students. But he is quick to offer some perspective. “The students find it pretty cool that we wrote it,” he says. “We didn’t write it. We adapted it and edited it and added stuff. But they take that as we wrote it, and so they think we’re just the greatest thing ever.”

Learn more about making an impact on Williston’s students and faculty