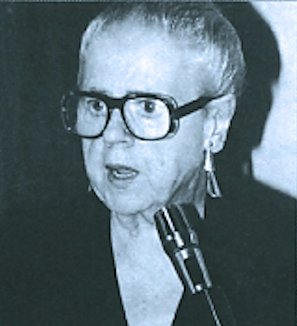

For a generation of Northampton School for Girls alumnae, the name of Hélène Paquin Cantarella (1904-2000) is one with which to conjure. Merely to write that she taught Senior English from 1958 to 1969 is to understate her influence. There is virtual unanimity among her former students that she was the most demanding teacher they ever had (her summer reading syllabus alone exceeded 30 titles), that her conversation, in and out of the classroom, was constantly challenging, that she urged and inspired her students to levels of production and insight of which they had never imagined themselves capable.

Perhaps her students caught only a glimpse of a life fully lived: she was prominent in the Italian anti-fascist movement during the War; taught at Smith College, where she founded the film program; was a prolific, nationally recognized literary critic and translator.

Hélène Cantarella frequently invoked “Noblesse Oblige”—the idea that with privilege came responsibility, that “for those who have been given much, much is required” (Luke 12:48). In a eulogy for Hélène, her friend, biographer (see below) and Northampton School colleague Ann Tracy wrote, “She seemed to believe that the world was perfectable, and so were we. That if we fought injustice, voted responsibly, elevated our minds with the best that humans have thought and spoken, and laid out the cocktail napkins for five o’clock—the list is not exhaustive—we would have made a start in the war against chaos. Her work at the school was in fact a distillation of a whole life spent in exhortation: think, read, learn, grow; keep up, speak up, straighten up, dress up; and love without stinting, carry on heroically, fight to the end.”1

Never one for reticence, Hélène Cantarella delivered the following remarks at a Williston Northampton Reunion on June 7, 1986. It is sobering to note how much still resonates 27 years later.

I

Noblesse Oblige: The Challenge of Educating Women

If Commencements are occasions for lofty pronouncements and eloquent exhortations to graduates about to enter into what is called “The Real World,” reunions, on the other hand, are times for what Marcel Proust—that great French chronicler of memories long lost—called “remembrances of times past.”

If Commencements are occasions for lofty pronouncements and eloquent exhortations to graduates about to enter into what is called “The Real World,” reunions, on the other hand, are times for what Marcel Proust—that great French chronicler of memories long lost—called “remembrances of times past.”

Those of you who were fortunate enough to read Les Cahiers de Marcel Proust with Miss Bement in French IV will recall how, one day, while having tea and a madeleine with his mother—as he had often done in his boyhood—Proust saw unfold in his mind’s eye the clear, jewel-like remembrances of people and events he had deemed lost forever in the mists of time.

So it is with me, as I look on your still young and lovely faces. The memories of what The Northampton School for Girls meant to me—and I hope to you—come surging to my mind and, in my own small way, I shall try to relive with you what were our dreams and aims under the eminently wise yet dynamic direction of its two great principals—Sarah Whitaker and Dorothy Bement.

But first, let us go back a bit further in time: Like every other American-born child, I was only dimly aware as I grew up in New Bedford, Massachusetts, where I was born, of the miracle of the American experience although my grandfather, who in his youth had known Abraham Lincoln, talked about it a good deal.

It was only during the six long periods of my life abroad, principally in France and in Italy, that I came to the full realization of its epic sweep, of what it had taken in terms of sheer, physical, intellectual and emotional courage, persistence and endurance, for our discoverers, explorers, and colonists to set forth from England in frail ships on the fearsome Atlantic, with wives, children and chattels, to sail toward a world unknown and uncharted, and, once established after unimaginable hardships, to pull up stakes again and set out through the hostile wilderness—in even frailer covered wagons—in search of new horizons and a better and freer life.

I also later became painfully aware, through my experiences as a student and teacher in the United States and Europe, how woefully ill-informed average American students are about their historical and cultural patrimony. I remember how often American teenagers, living and studying abroad (as they did then and do now), when pressed by their European or Asian schoolmates for specific information on some aspect of the American political scene or some literary movement, were hampered by a lack of concrete knowledge—a fact they themselves recognized and deplored.

It was not then—nor is it now—entirely their fault, if fault there is. Students in the United States, particularly at the high school level, have too long been under-challenged and under-educated.

I was quite convinced that most were intellectually able to cope with far more taxing subject matter than what was being offered in most curricula, and that most were generally willing—timidly at first, perhaps, but with increasing interest—to respond to any challenge put to them.

That is why, when Mrs. Adah Judd Green—here among us—retired, and suggested me as her successor in English IV, I accepted with enthusiasm—and some apprehension. Would I measure up to my eminent and much-beloved predecessor? I would try.

I found you beautifully prepared. You had been taught in depth how to read beyond the mere lines of a poem, by that gentle, poetic, yet wry blithe spirit, Violet Hussey; and, under the inspired teaching of Grace Carlson—then Dean of the School and Chairman of the English Department—you had learned to appreciate the majestic beauty of the English language while recognizing it also as an incredibly flexible instrument for the expression of the most evanescent of human emotions. I had only to continue building on those solid foundations.

Here was the chance I had long wanted..to try to share what I myself had learned and—through the mémoirs, documents and literary works left us by our forebears—to rediscover with my students our common heritage of wisdom and fortitude. In the bargain, I would repay the enormous debt I owed my ancestors and my parents for having bestowed upon me the priceless boon of my North American heritage.

It was a large order. I admitted it to you then and I still think so today. Yet, you were the first to agree that the rather forbidding syllabus was not beyond you. Perhaps it was because you realized that your senior year was to be a time of vital decisions during which you would be called upon to assess your academic achievement in terms of your immediate future. Be that as it may, I found you eager to face the cost in terms of effort and good will.

When your spirits flagged—as is natural—I would remind you that much had been given you in life and that life has a way of exacting as much in return. Hence my oft-recurring reference to that staunch old French heraldic battle-cry: Noblesse Oblige.

Do not forget that yours was a difficult era—the blindly rebellious ’60s. And, as “jeunes filles en fleur,” emerging from the chrysalis of adolescence into young adulthood, you were often torn between the contradictory need to be looked upon individually, as unique specimens, while, at the same time, feeling confused by an equally impelling desire not to stand apart, to be one of “the crowd”—part and parcel of “the group.” What I wanted above all was to make you see yourselves not as the ab ovo off-shoot of your own “One Single Decade,” but as the sum total and end-product of our national experience, in which each one of you had her own individual place but among others.

In short, what I sought to do with you, for you, and, at times, against your wills, was to make you fly, like Icarus, into the blazing sun of knowledge and rise to the full realization of your potential.

I recognized that you would represent a new challenge for me and, by the same token, that I would be nothing less for you. But challenge comes with the turf. I demanded the very best that you could give, and you demanded—and got—the same from me.

So, together—not without trepidation on your part and mine—we set forth on our year-long hegira, which would take us on a four-hundred-year journey from a tormented 17th-century England with our Discoverers and Explorers. We then traveled to Massachusetts with the stern, intrepid Pilgrims, to Pennsylvania with the Quakers, then back to Massachusetts to see through the eyes of Increase and Cotton Mather—and Hawthorne’s, too—what life was like in that theocratic State. We later shared in the troubles that led to the Boston Tea Party, our War of Independence, and studied the documents left us by our own great men of the Enlightenment who formed, what still is today, the world’s most effective democratic Constitution.

Heartened by having won peace with England, as well as independence, we set off on a transcontinental trek with the Pioneers of the Great Migration Westward, took part in the opening and astonishing growth of the Northwest and the rise of America’s middle class, the crash of the Chicago wheat market and its impact on the economy of the late 19th century.

Then, back East again for a flying visit to the Boston and Cambridge Brahmins and the budding élite of New York’s Social Register. Spurred on by the call of the sea, we embarked on the Pequod with Captain Ahab and his motley crew for the odyssey in search—not of the Golden Fleece—but of Moby Dick, The Great White Whale.

Once safe back on terra firma, we shared in the Stock Market Crash of 1929, the Great Depression and the ensuing Second Great Migration this time of the drought-stricken Oakies from the Dust Bowl to California.

By way of contrast, we looked in briefly on the Jazz Age before sailing to Europe with our young 20th-century Expatriates in quest of their identities.

Finally, we brought our great voyage to a climax with Walt Whitman, whose poems, in their epic sweep, synthesized for us what America, its democracy, its liberties, its aspirations, its common man, are all about.

II

A quarter of a century has slipped by since I bade you farewell in Northampton on graduation day. Much has happened between then and now. You have evolved gracefully from embattled members of the “Me Generation” into handsome, full-fledged young-upward-mobile-professionals — in today’s acronym, YUPPIES — with all the accoutrements of that privileged station in life.

The world, during that same period, has changed too. For many of us, for the better; for too many others, for the worse. Your generation, and mine too, find ourselves facing problems of unprecedented complexity and magnitude.

For one thing, we live in a rapidly shrinking world, in which distances have been abolished. The Concorde can whisk you from New York or Washington to Paris or London in something less than two hours. Intercontinental missiles need only minutes.

Frontiers — save for customs and immigration officers — have lost their meaning. Neither are there now, as in the past, any mutually-recognized “front lines of combat,” far from civilian centers. The war-ravaged Middle East is giving continuing proof that today’s battlegrounds are the streets, marketplaces, public buildings, residential districts, slums, airports and stadiums of the world’s great capitals.

The Chernobyl disaster further proved that in our nuclear age, no continents, no nation, no man, no woman, no child, can henceforth be an island. If you entertain any doubts on this score, ask the people living in the most remote regions of Afghanistan, Cambodia, or Central America.

It immediately became evident that what had happened at Chernobyl could not be kept secret even by the Soviets, those masters at concealing adverse news. Even less could Chernobyl’s effects be contained within the borders of even so vast a country. Russia’s radioactive ozone swiftly became Scandinavia’s, then, pushed by strong winds, drifted halfway across the world, taking with them their deadly load of deadly elements.

Nobody can hope to remain immune. Acid rain falls on the rich as well as the poor, on Americans as well as Canadians. We are all in this together — living — as it were — in one another’s back yard, members of one vulnerable global village.

Can we afford to turn our backs on any of this? Not any more than we can continue to ignore with impunity the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse—War, Famine, Plague and Death by Violence—as they thunder over our country as over the rest of the world.

Never before have the world’s great powers become engaged—not yet by direct involvement (since the recognized the terrifying risks of that foolhardy gesture to themselves as well as to the enemy)—but by instigating and supporting surrogate wars here, there, and everywhere, for geopolitical aims never fully made clear to the citizenry.

Never, either, have so many famine-stricken populations been herded into dehumanizing forced re-settlements—especially in Ethiopia, South Africa, and the Sudan—and left to roam without food, water, or shelter, over parched, arid wastes, prey to slow death from exhaustion, dehydration, starvation and disease.

These are not isolated phenomena. They are, to varying degrees, part and parcel of every nation’s life today. Read the daily press or turn on the nightly news broadcasts and you will see and hear that we, in the United States, have not been spared. Hunger, in another guise, stalks this land too. Our great urban centers have their uncounted hordes of wandering homeless poor for whom, ironically enough, the world’s richest nation cannot afford to provide even elementary food or shelter.

Like everyone else, we have our quota of mysterious, newfangled plagues. I need mention only Legionnaire’s syndrome, MS, cancer, AIDS, which today still defy all medical solutions… not to speak of such self-inflicted scourges as cocaine and now, crack.

As for the specter of death by violence, it stalks every last one of us subliminally by day and in the dark of night. Yet, never has sheer, naked, gratuitous violence been exalted as it has today. The media thrive on it—blatantly. We batten on it during our leisure hours. Yet, when this same senseless violence spills over from TV and movie screens into the realm of real life, we are horrified.

But, think for a moment: Isn’t the problem of our own making? What sells at the box-office? What TV shows get the highest ratings? What sells best at newsstands? The staid, reliable New York Times or the tabloids, with their sensational, lurid tales of murder, rape, and other forms of mayhem? Why have Dallas and Dynasty, those epics of conniving corporate and dynastic savagery, become not only world-wide favorites but universal trend-setters?

Because we patronize them. And box-office receipts and TV ratings—those infallible barometers of popular taste for show business—determine what we get.

It lies in our power to correct some or all of this if we are willing to take the time and trouble to let our protesting and more selective voices be heard. It is another of those humble grass-roots jobs that require time, thought, courage and action. But it does work.

Somewhere, somehow, some answer, some solution must be found to our problems. In the last analysis, it is up to us to find both. Given the immensity of their mind-boggling proportions, you may well be tempted to ask, “What can one, single, person do? What possible difference can I make?

History provides us with countless examples of single individuals who did, and still do make a difference. I shall spare you my list. But choose your own rôle-models and walk in their footsteps.

My counsel to you would be to keep abreast of civic, national, and international affairs, especially the rôle we—as a people and as a nation—play in their outcome.

Protest when things go wrong, even if it entails standing up and being counted.

Practice by word and deed what you believe in, expressing your opinions, preferably by letter, bearing in mind that verba volant, scripta manent.2

Insist on the upgrading of education in our public schools, in order to make our underchallenged youth—rich and poor alike—to master the ever-more demanding skills they must have if they are not to drift hopelessly into permanent unemployment through functional illiteracy.

We must also learn—all of us, young and old alike—to transcend the deep-rooted religious, racial and cultural prejudices which tear at our body politic. We have the needed instruments at hand. We must make them work and use them effectively.

Lastly, it is imperative that we start thinking beyond the old, rigid concepts of territorial rights and see mankind for what it is: One, living, pulsating unit made up of human components sharing the same need for basic human rights. There would seem to be no alternative if we are not to perish en masse.

Either we learn—no matter how hard it is—to live together in relative and reasonable understanding and tolerance (no one asks for harmony) or we risk blowing this world to smithereens with the incredibly swift and deadly nuclear armaments all of us are amassing relentlessly.

Man has always aspired to the ideal of one world. Well, we’ve got it! Man’s inventiveness and ingenuity, abetted by modern science, have seen to that. Let us not be lured away from trying to improve it here on earth for everybody—by dreams of inter-planetary pie-in-the-sky. This earth of ours—this globe—is the only planet we really have.

Besides, it is also the only one we really know anything about. When all is said and done, it is still, after untold millennia, the only planet that homo sapiens has found tolerably habitable.

Let’s get to work trying to save it…and ourselves…

Noblesse Oblige

Notes:

1Ann Tracy, remarks at Hélène Cantarella’s memorial service, December 16, 2000. Typescript, The Williston Northampton Archives.

2“Spoken words fly; writing remains.”