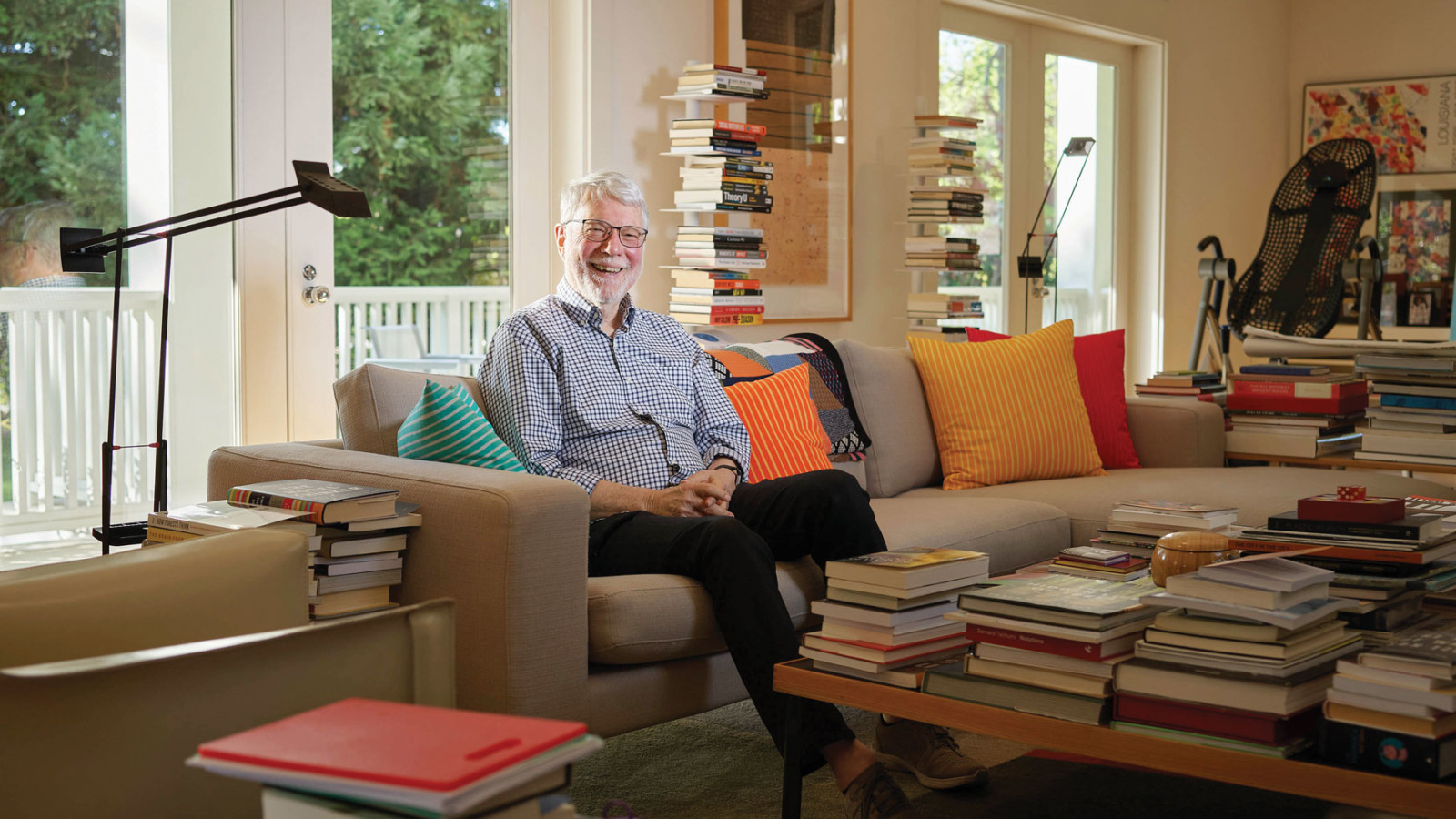

After a lifetime of radical innovation, John Seely Brown ’58 continues to look to the future of what’s possible

Back before the pandemic put such things on hold, the scientist, researcher, and management theorist John Seely Brown ’58 was speaking at a big tech conference near his home in California. His topics included the rapid pace of change in our hyper-connected digital age, and he touched on some of the technologies that are radically reshaping life and work: artificial intelligence, intelligent augmentation, big data, cognitive computing, deep learning machines, the Internet of Things, the Internet of Internet of Things, blockchain, and biotech, among others.

When he finished his talk, someone in the audience asked what a kid starting college today should study. Without missing a beat, Brown, who majored in physics and math at Brown University and earned his Ph.D. in computer and communication sciences from the University of Michigan in 1970, replied, “Oh, absolutely tell him to go into history.”

The answer produced something rarer than a Silicon Valley unicorn: a packed house of technologists and venture capitalists stunned into silence. But anyone who knows Brown, or JSB as he is widely known in tech circles, would not have been surprised. In a pioneering career that has spanned the advent of the PC to the latest developments in cloud computing, he has succeeded by seeing connections —and possibilities— that others can’t imagine.

A longtime chief scientist of Xerox Corporation, JSB for more than two decades directed the company’s Palo Alto Research Center, the storied lab whose inventions include the graphical user interface (i.e., point-and-click navigation with icons), laser printing, distributed workstations, the spell checker, and the Ethernet. “Our mantra was,” he says, “‘Invent what you need but always use what you invent.’”

He credits his lifelong eagerness to play with ideas in part to his experience at Williston. “I remember some of my teachers from back then more clearly than any teacher I had at Brown,” he says. For a while he even felt disappointed in college because he didn’t think he was learning as much. “The teachers at Williston were willing to work with me, to listen to how I was trying to understand something and challenge me in productive ways. They were attentive to the idiosyncrasies of each kid and wouldn’t freak out at being asked some dumb question. They would say, ‘OK, let’s work on this together.’ There was a sense of learning as a form of play. To me, that’s what education is about. And don’t forget, the head of my floor for at least one year had a Ph.D. in science. I could walk down there any evening and have a conversation.”

Since retiring from Xerox in 2002, JSB has remained a driver of innovation as a visiting scholar at the University of California and independent co-chairman of the Center for the Edge at Deloitte, the global management consulting and business services company. The latter’s mission is to help executives operate at the intersection of technology and commerce. As JSB puts it, “We conduct original research on emerging business opportunities that are not yet on the CEO’s management agenda but should be.”

A member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the National Academy of Education, a fellow of the American Association for Artificial Intelligence, and a MacArthur Foundation trustee, he has served on numerous corporate boards, including Amazon, for the past 14 years. The nine books he has written and co-authored include the seminal The Power of Pull: How Small Moves, Smartly Made, Can Set Big Things in Motion (Basic Books, 2010). Its many fans include former Google CEO and Chairman Eric Schmidt, who said, “If you want to meet the challenges of living and working in the future, this book should be your guide.”

The future is JSB’s special subject. He spends serious time thinking about how the digital tools he helped introduce are reshaping society at a dizzying pace. In the past, he says, when a new technology was introduced, it would be integrated over the course of a few years and then tended to stick around for a several decades until the next new thing came along. That interval no longer exists. The average life span of a new phone app, he notes, hovers around 30 days. We live in an age of never-ending change, a kind of Cambrian explosion of technology.

To illustrate the seismic transformation underway, JSB offers a metaphor inspired in part by his love of adventure sports. For his parents’ generation, he says, things moved along at the stately pace of a steamship. “They set course, fired up the engines, and powered ahead. The survival strategy was to practice a lot of steady persistence.” Then came the early digital age; change was faster but still manageable. To keep up, you played the wind like the skipper of a sailboat, tacking one way and then another to get where you wanted to go. But now the environment has shifted again, the flow of information quickening and becoming more turbulent. Navigating today’s dense information stream requires the skills and agility of a whitewater kayaker, who must constantly interpret rapids to get a picture of what lies hidden beneath the surface. “I like to say we really shifted from reading content to reading context,” he says. “If you are a whitewater kayaker, you learn to read context. Otherwise, you’re dead.”

All of which was on his mind at the conference, when he blindsided the futurists by extolling the study of history. “I kind of surprised myself a little bit when I said that,” he admits. “I was reflecting on the techniques needed to read context. How do you understand how to fill in the missing pieces? It was a history teacher at Williston who got me to pay more attention to the context of events. A research historian knows how to probe and fill in holes until a picture emerges, ‘Oh, this makes sense. Yeah, this could be it.’ They understand how to unravel the forces that were in action at a moment of time, most of which were more or less invisible as they occurred.”

JSB calls the technique “sense-making through imagination,” and he says it requires a mix of humanities and math and science folded together in interesting ways that build webs of connections and allow us to fill in blind spots. Machine intelligence alone is insufficient to the task, he says, citing Brexit and the 2016 election as recent events that experts armed with potent algorithms failed to see coming. “A lot of us thought we understood how to read the signals, but we did not read the context right. That’s to say data analytics—which many of us worship, starting with me—can’t do everything. Imagination closes the gap between what is novel and what is known. Imagination allows us to see beyond what our present assumptions define as possible.”